Richard Prince and the Increasingly Permissive Treatment of Infringement

Earlier this month, a federal judge in New York denied a motion to dismiss a copyright infringement suit against notorious “Instagram artist” Richard Prince, setting the stage for another transformative fair use showdown. The lawsuit is the latest turn in an ongoing debate—often involving Prince or similar artists—over what qualifies as transformative in the digital age, as more and more artists engage in acts of appropriation with questionable amounts of added expression. And while it appears the District Judge in New York may not subscribe to a broad interpretation of the limits of fair use, a significant win for Prince in the Second Circuit and the seemingly limitless application of the transformative purpose fair use theory represent a continuing slide towards an increasingly permissive approach to copyright infringement.

Whether an act of appropriation is sufficiently transformative of the underlying work as to weigh in favor of non-infringement under the first fair use factor is one of the thorniest issues in copyright law. It’s often an exercise in subjective consideration not unlike a determination of what qualifies as art—which is a question that will never be answered by any bright line rule. What one sees as a significant addition of transformative original expression, another may deem a meaningless add-on that does nothing to enhance or alter the underlying work.

A Career in Copying

Enter Richard Prince, an artist who’s made a very lucrative career out of appropriating the photographs of others. In many instances, Prince’s additions to the photos he uses would be considered negligible, and he, like other appropriation artists, such as Jeff Koons, who operate in this grey area of artistic reprocessing, has incurred a good share of criticism and a handful of copyright infringement lawsuits.

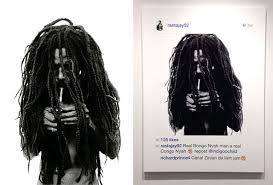

The current case against Prince is one of many lawsuits stemming from a 2014 exhibit in which he displayed blown-up prints of others’ Instagram posts without the permission of the account holders or photographers, selling some of the images for upwards of $100,000. Prince’s original contribution to the underlying works was a mere enlarging of the posts, though in some cases he added a comment under the images. In 2015, Donald Graham, one of the photographers whose works were featured in the exhibit, sued Prince and the gallery hosting the exhibit for copyright infringement.

Prince and the Gagosian Gallery petitioned the court to dismiss Graham’s complaint, arguing that the resulting works were transformative and qualified as fair use. But earlier this month, District Judge Sidney H. Stein denied the motion to dismiss, finding that “[t]he primary image in both works is the photograph itself,” and that “Prince has not materially altered the composition, presentation, scale, color palette and media originally used by Graham.”

Though this preliminary win for Graham seems like a good sign of the Court’s skepticism regarding the transformative nature of Prince’s works, Judge Stein acknowledged that in order to determine whether Prince’s alterations gave a new expression or meaning to Graham’s original work, the court would have to consider factors such as art criticism and Prince’s statements of his intention. But considering art criticisms is an inexact and often subjective test of the transformative nature of a work, and it’s one that has resulted in findings of fair use for Prince’s equally negligible transformations in the past.

In 2008, Prince faced a similar complaint based on his permissionless appropriation of a series of photographs taken by Patrick Cariou. Of the 35 recycled images in Prince’s exhibit, most featured minimal alterations that few would consider to be a comment on, or criticism of, the underlying work. In 2011, the district court found that Prince’s works were not fair uses of Cariou’s photographs and that Prince was liable for copyright infringement for every work misappropriated. But following an appeal by Prince, the Second Circuit reversed the district court’s decision, holding that a majority the works were transformative examples of fair use.

The Court insisted that Prince’s “composition, presentation, scale, color palette, and media are fundamentally different and new compared to the photographs.” Also important to the Court’s decision was the idea transformative nature of a work need not be determined by an artist’s stated objective of transformation, or lack thereof.

Explaining that “[r]ather than confining our inquiry to Prince’s explanations of his artworks, we instead examine how the artworks may ‘reasonably be perceived’ in order to assess their transformative nature,” the Court essentially concluded that transformation is in the eye of the beholder. Unfortunately, recent trends seem to be conditioning the beholder to ignore what was once considered misappropriation.

Infringement as the New Norm

Regardless of whether Prince’s works are found to be fair use or infringement in the current case, the Second Circuit’s reversal represents a continuing slide towards a more accepting attitude towards copying. If Prince continues to slavishly reproduce the works of others, which—judging from some unabashed tweets—he seems to have every intention of doing, it’s likely that he will eventually jump on the transformative purpose bandwagon to claim his work is fair use.

At a time when courts and critics are validating more and more acts of copying of entire works of authorship when the alleged infringement serves a purpose different than the original, it’s plausible that appropriation artists will try to adopt similar arguments. Prince might claim that his exhibition of Instagram posts serves an important public interest by exposing them to the general public, not just a limited number of social media followers. It may seem like a tenuous construction, but the reality is that transformative purpose fair use has been poorly defined and is increasingly subject to expansive interpretations that could support such an argument.

And then, of course, there is the inevitable argument that enforcing copyright and opposing these broad interpretations of fair use will have a chilling effect on artists like Prince and rob the world of creativity. In response, I’d urge advocates of this position to consider Andy Warhol, perhaps the most revered “pop” artist of all time. Warhol often appropriated others’ images into his works, and eventually was sued by a few photographers whose works he reused. But as a Warhol historian recounts in an article about the artist’s reaction to the lawsuits, “Warhol decided that he would rather use his own images when he could, which inadvertently launched him into experimenting with a new medium — photography.” Perhaps in today’s copyright landscape, Warhol would never have picked up a camera.

The bar for the level originality required by work of authorship to qualify for copyright protection is rightfully set low. It’s a testament to the idea that we do not believe our Copyright Office examiners or government officials should be making subjective judgments on the artistic merit of a given work. But when someone sets out to build upon the work of another, the fair use doctrine requires a showing of meaningful transformation, especially when the whole of the original work is appropriated for a commercial purpose. Another win for Prince would betray the spirit of legitimate appropriation, giving further momentum to an amorphous transformative fair use theory and the unfortunate trend of copyright infringement tolerance.